NOAA’s Arctic Vision and Strategy

National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration

January 2025

NOAA Arctic Executive Committee

Kelly Kryc, Ph.D.

Chair of Arctic Executive Committee, Arctic Senior Advisor, NOAA Headquarters

Robert Foy, Ph.D.

Science and Research Director,

Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service

Alaska Regional Coordinator, National Ocean Service

Sandy Lucas, Ph.D.

Director, Arctic Research Program, Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing, Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research

Scott Lundgren

Director, Office of Response and Restoration, National Ocean Service

Director, Office of International Affairs, NOAA Headquarters

Donald Moore

Director, Alaska Environmental Science and Service Integration Center, National Weather Service

Kaitlyn Montán

Director, Office of Legislative and Intergovernmental Affairs, NOAA Headquarters

Office of General Counsel, NOAA Headquarters

NOAA Liaison to NORAD/USNORTHCOM, Office of Marine and Aviation Operations

Chief of Staff, National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service

Chair of Arctic Action Team, POC to the Arctic Executive Committee, Office of Coast Survey

NOAA Arctic Writing Team

NOAA Arctic Executive Committee

David Allen

Arctic Research Program, Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program, OAR

Mikayla Basanese

International Activities Office, OAR

John Bengtson, Ph.D.

Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NMFS

Kaja Brix, Ph.D.

Alaska Regional Office, NMFS

Ludovic Brucker, Ph.D.

Center for Satellite Applications and Research, NESDIS

Jessica Cherry, Ph.D.

National Centers for Environmental Information, NESDIS

Geoffrey Dipre, Ph.D.

Office of International Affairs, NOAA HQ

Cynthia Garcia, Ph.D.

Arctic Research Program, Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program, OAR

Chelsea Gray, Ph.D.

Office of International Affairs, Trade, and Commerce, NMFS

Rebecca Heim

Alaska Region Headquarters, NWS

Patrick Hogan, Ph.D.

National Centers for Environmental Information, NESDIS

Allison Lepp, Ph.D.

Arctic Research Program, Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program, OAR

Scott A. Miller

Alaska Regional Office, NMFS

Eliza Mills

Executive Affairs Division, OMAO

James E. Overland, Ph.D.

Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, OAR

Lauren Talbert

Policy Office, NOS

Meredith Westington

Office of Coast Survey, NOS

Executive Summary

“The significance of understanding the Arctic continues to grow, in terms of the lives, livelihoods, and lifestyles of all Americans. Since NOAA’s last Arctic Vision and Strategy was released in 2011, the Arctic environment has evolved into a drastically different state. Warming and expeditious sea-ice loss have triggered cascading ecosystem responses, with pronounced changes observed deep into the ocean, throughout the atmosphere, along Arctic coastlines, and across the land.

This Arctic in transition presents unprecedented opportunities in the northern high latitudes, along with unfamiliar challenges: significant economic impacts driven by shifting fish stocks, national security concerns, and increased need for emergency response and preparedness.

With this Vision and Strategy NOAA cements its commitment to embrace these new opportunities, to maintain robust and ethical research activities in the Arctic, and expand products and services to empower Arctic communities navigating unprecedented challenges. We emphasize the need to work early and continuously with partners from communities and industries throughout the region, as well as with private and non-profit entities, and public agencies at all levels. Strengthened by partnerships at home and abroad, we will embrace these new opportunities and ensure communities can thrive in this new Arctic.”

The Honorable Dr. Richard W. Spinrad

The Arctic stands at a critical transition point, warming three times faster than the global average1 and triggering cascading effects that reach far beyond its boundaries. These changes challenge the Arctic’s delicate ecosystems and the communities that depend on them, while profoundly influencing weather patterns in mid-latitudes and climate systems worldwide. Arctic communities face unprecedented challenges – from coastal erosion and thawing permafrost threatening entire villages to changes in the health and migratory patterns of wildlife and fish that disrupt sustained access to food and cultural resources. The Alaska seafood industry’s 2022-2023 $1.8 billion total direct loss2, in part due to climate change effects, illustrates the social and economic stakes as fishing communities struggle to maintain social networks, well-being, and livelihoods. Furthermore, retreating sea ice opens new shipping routes, increasing concerns about marine plastics and debris and raising complex security considerations. For the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), these intertwined environmental, economic, and social challenges demand coordinated, rapid, and innovative responses.

NOAA’s vision for the Arctic is focused on building resilient ecosystems and communities through science-based decision-making, partnerships, and environmental stewardship. This vision aligns with NOAA’s broader commitment to: build a climate ready Nation and promote economic development while maintaining environmental stewardship. In support of this vision, NOAA’s mission is to understand and predict our changing environment, from the bottom of the ocean to the surface of the sun, and to manage and conserve America’s coastal and marine resources. NOAA’s presence, and the work that it conducts, are crucial to understanding changes in the Arctic climate and ecosystems, predicting future climate and its impacts, providing information services such as charting and forecasting, and supporting local communities and economies to be resilient, sustainable, and productive. NOAA has the capabilities to address emerging issues, yet current threats to the environment, society, the economy, and national security will continue to grow, necessitating greater resources to address growing challenges. A strategic approach that leverages NOAA’s existing strengths and growing priorities, as well as those of regional, national, and international partners, is critical.

To address current and emerging challenges in the Arctic, NOAA has developed a strategic framework organized around three pillars and six priority goals needed to realize the vision of resilient ecosystems, communities, and economies.

-

1. Advance Environmental Science

- Goal 1: Strengthen Foundational Science

- Goal 2: Monitor and Forecast Sea Ice

- Goal 3: Improve Weather, Water, and Climate Forecasts, Warnings and Impact-Based Decision Support

-

2. Promote Collaborative Stewardship

- Goal 4: Enhance Partnerships- International, National, Regional, and Local

- Goal 5: Conserve and Manage Arctic Coastal and Marine Ecosystems and Resources

-

3. Support Resilient Communities

- Goal 6: Advance Resilient and Healthy Arctic Communities and Economies

Developing and executing the goals and actions identified here requires a coordinated approach across NOAA’s line and staff offices and collaboration with other Federal agencies, the State of Alaska, local communities, Indigenous, Peoples, and international partners. The NOAA Arctic Executive Committee will continue to provide leadership to achieve these goals and will guide development of related engagement and a detailed budget strategy. Success requires dedicated resources and robust partnerships. It also requires an unwavering commitment to scientific integrity, innovation, and collaboration. NOAA remains steadfast in ensuring our work in the Arctic serves the needs of all Americans while contributing to global understanding of this crucial region.

Definitions

Introduction

An Arctic in Transition

From the seafloor to the surface of the sun, NOAA’s critical data and observations form the basis for daily weather forecasts, climate predictions, and ecosystem understanding worldwide. They underpin the nation’s ability to understand and predict changes in ocean circulation and sea ice extent, track environmental changes allowing for improved management of fisheries and other living marine resources, and help protect life and property. NOAA provides an ever-expanding suite of essential products and services that drive the economic vitality of the nation and provide community leaders, planners, emergency managers, and decision makers on all spatial and time scales with trustworthy, timely information. NOAA is committed to building a Climate Ready Nation in all regions of the United States and accelerating growth in an information-based Blue Economy.

NOAA’s core tenets of science, service, and stewardship converge in a unique and profound way in the Arctic. While geographically remote, the region’s influence extends globally, acting as a barometer of change and a thermostat to stabilize Earth’s climate by reflecting sunlight and moderating global temperatures. The temperature effects of anthropogenic climate change in the Arctic are amplified at three times that of the rest of the globe. No facet of the Arctic system is currently untouched by these changes, and isolated impacts have widespread effects from the inherent interconnectedness of culture, society, economy, and environment in the region.

At the forefront of Arctic change are Indigenous Arctic communities. For more than 10,000 years, Indigenous Peoples within the Arctic have amassed an immense amount of knowledge and understanding of the ecosystems of which they are a part. Indigenous Knowledge, including insights and proven holistic approaches for mitigation and adaptation measures, is an invaluable necessity to advance our collective understanding of Arctic change and strengthen community resilience. NOAA will continue to work with Indigenous and local communities affected by the rapid changes in Alaska and the Arctic.

Since the release of NOAA’s first Arctic Vision and Strategy11 in 2011, the Arctic has transformed dramatically. What began as early signs of change — including increasing air and ocean temperatures, thawing coastal and inland permafrost, loss of sea ice, ocean acidification, and shifting marine ecosystems — has accelerated into a fundamental transformation. It was clear that these emerging changes could cause further critical environmental, economic, and national security issues with significant impacts on Arctic communities, economies, and livelihoods. Global implications of Arctic climate change, however, were uncertain, and activities outlined in the original Vision and Strategy therefore prioritized improving the ability to understand and predict those changes and implications. The time for action in the Arctic is now under this new Vision and Strategy.

The Arctic is changing and it is changing rapidly.

In the Arctic, rapid environmental and ecological changes, coupled with extreme events (e.g., wildfires, major sea ice loss, storms, and ecosystem shifts) have wide-reaching and cascading impacts, but also present new opportunities, both of which require NOAA’s commitment to the region. While concerns in the 2011 Arctic Vision and Strategy focused primarily on sea ice loss, today’s challenges demand an increase in Arctic investments and a more comprehensive approach that recognizes the interconnected nature of Arctic systems. The need to accurately anticipate future environmental changes, provide marine and ice services for safer shipping, predict associated impacts to Arctic integrated ecosystems, and determine the role of Arctic climate dynamics in weather patterns in the contiguous United States and beyond is urgent, as is the need to equip communities with the knowledge, tools, and resources required for climate preparedness. NOAA’s mission in the Arctic will, therefore, adapt to address large, overarching questions to inform NOAA’s 1) understanding of the current state and change of Arctic environments and its ecosystems through working with Indigenous governments and communities, 2) working with underserved communities, and 3) ability to predict how this region will continue to evolve as a result of a changing climate. In doing so, NOAA will be better equipped to provide relevant products and services that communities, governments, and businesses rely on, and support growing demands from the transportation industry, emergency management sectors, and homeland security to meet the unique challenges of an Arctic in transition.

Evidence of Change and Key Questions for an Arctic in Transition

- Open water areas coupled with increased ocean heat storage potential as sea ice cover continues to diminish are in large part driving the Arctic to warm at a rate three times faster than the global mean12, a phenomenon referred to as Arctic amplification. Decadal trends of sea ice decline and subsequent increases in ocean heat storage are known, yet the processes and mechanisms by which the impacts of Arctic amplification are affected by internal climate variability remain poorly understood, limiting NOAA’s ability to forecast the compounding effects of climate change in the Arctic. How does natural atmospheric variability contribute to Arctic amplification and extreme events, and how could this interplay evolve as the Arctic continues to warm?

- Unprecedented warming and extreme low sea ice extents during the winters of 2018-2019 prompted the largest Bering Sea climate and ecosystem events in recent history, which were characterized by jet stream meanders and warm sea temperatures, northward pollock and cod movements, ecosystem species shifts, and unusual marine mammal mortalities and strandings. The resulting societal impacts, including the fisheries closures due to drastic declines of snow crab13 and northern salmon stocks14,15, were catastrophic. This profoundly affects commercial and subsistence fisheries with lingering effects on people who rely on marine resources for food, culture, and social and economic well-being. While the Bering Sea has since returned to more typical sea ice extent conditions, future low sea ice events, and pronounced, widespread boreal conditions are expected. What are the primary drivers of these events, and how frequently will they occur?

- Drastic changes currently occurring in the Arctic are connected with adverse weather in mid-latitudes, including California droughts and cold winter events in the eastern and southern United States and Asia16. Interactions between local Arctic temperature increases and the meandering of the jet stream and polar vortex are currently poorly understood. Case studies support the linkages to extreme events, and additional research is needed to make improvements to sub-seasonal forecasts. How will further warming and climate change in the Arctic continue to alter weather patterns in the contiguous United States and globally?

- Fueled by steady increases in temperatures, multiple unprecedented extreme events indicate major Arctic change is underway. Such new extremes include marine and terrestrial heatwaves, wildfires, enhanced carbon dioxide and methane emissions of the arctic tundra, surface melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet, devastating storms like Typhoon Merbok in 2022, and ecosystem reorganizations with impacts on economies, cultures, and lifestyles. How can NOAA observe, model, and understand these events while more effectively working with Arctic knowledge holders to guide the necessary research questions and determine the resources needed to ensure community resiliency against these extremes?

NOAA’s current work in the Arctic is far-reaching, including satellite and in situ observations, new data gathering technologies, ice and snow forecasts, weather forecasts, international collaboration, biological surveys, nautical charting, and response and restoration. However, with fundamental Arctic systems research needs in mind, it is clear that a holistic approach to NOAA’s Arctic activities is required to support its ability to maintain national and global leadership in marine, terrestrial, and atmospheric research and stewardship, as well as for NOAA to continue providing timely, relevant, and impactful products and services to the residents of Alaska and the country. A holistic approach can only be achieved through ambitious and sustained investments in science, technology, and infrastructure with partnerships from international to local scales. This includes sustained funding for Indigenous and local communities to be involved in monitoring, research, and decision-making. Through this concerted effort, NOAA can better serve Arctic communities while advancing key national priorities such as those outlined in the amended Arctic Research and Policy Act of 198417, U.S. National Strategy for the Arctic Region18, the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee Arctic Research Plan19, and U.S. Government Arctic Strategies.

NOAA’s Arctic Vision and Strategic Framework

NOAA envisions an Arctic where the results of sound science, including accessible data, are made rapidly and widely available to inform decisions and actions related to conservation, planning, management, and adaptation. This will, in turn, support healthy, productive, and resilient ecosystems, communities, and economies.

To achieve this vision, NOAA’s Arctic mission will prioritize six integrated, cross-cutting goals developed and vetted across NOAA’s Line and Staff Offices and derived from NOAA’s urgent mission needs (Fig. 1). These goals follow three overarching strategic pillars: 1) Advance Arctic environmental science to provide a foundation of improved research and understanding of ecosystem and climate change in the Arctic, 2) Promote increased cooperation and collaboration with partners for coordinated stewardship of ecosystems and resources, and 3) Support and foster resilient and thriving communities and economies.

Figure 1. NOAA Arctic Vision and Strategy strategic pillars and goals for achieving a resilient and thriving Arctic.

Each goal is presented with the following information:

- A Goal Statement — What it expects to achieve and how

- Its Strategic Importance

- Current Activities already underway to achieve the goal

- The Five-Year Strategy to achieve the goal, followed by Specific activities needed to achieve the goal

Each goal, detailed in the following sections, addresses urgent and timely issues by providing the information, knowledge, policies, and services needed to meet NOAA’s mandates and stewardship responsibilities and enable communities to live and operate safely in the Arctic. The goals reinforce each other, fulfill and integrate national and international objectives, and establish, enhance, or leverage partnerships with other Arctic nations, international organizations, government agencies, the State of Alaska, non-governmental organizations, academia, and local communities. NOAA’s work in the Arctic relies on partnerships, including its ongoing relationships with Tribal entities in Alaska.

Goal 1: Strengthen Foundational Science

Goal Statement: To advance Arctic knowledge by leveraging innovative research methods, filling gaps in observational data, conducting robust data analysis and modeling, and committing to broad data accessibility and ethical usability to enhance Arctic system understanding and support communities, scientists, and decision-makers navigating an Arctic in transition.

Strategic Importance: While scientific strides have been made to advance understanding of Arctic systems interactions, the current rate of change and breadth of environmental responses to change in the region underscore the need to maintain and strengthen NOAA’s foundational science.

Increasing extreme events, complex weather interactions between the Arctic and mid-latitude regions, and profound ecological shifts in both the land and ocean represent prominent scientific challenges with regional to global impacts. To address these challenges, NOAA must prioritize the foundational operational and research activities that target observations and modeling at the intersections of Arctic systems (e.g., marine ecosystems, sea ice dynamics, atmosphere-land-ice-ocean interactions [see Goal 2], and others). Insights gained through such observations and modeling are critical for model improvements, initialization, calibration, and validation that allow NOAA to predict future Arctic changes and forecast associated impacts more accurately.

Sustained observations form the backbone of NOAA’s products and services in the Arctic. NOAA’s foundational Arctic observational capabilities span from a sustained, coordinated, and integrated network of satellites, remote sensing, and in situ observing systems to the collection of physical, chemical, and biological samples, propelled by continued development of new technologies, such as low-cost and autonomous sensors that can be deployed on a variety of platforms of opportunity. NOAA’s capability to understand oceanic, land, and atmospheric processes in the Arctic in order to model and forecast changes, including associated ecological responses and impacts to Arctic communities, rests on the quality, continuity, and spatial coverage of observation data. Proactive management strategies for existing and forthcoming data will greatly extend the reach and impacts of NOAA’s foundational science activities, including the application of artificial intelligence technologies. By strengthening foundational science, NOAA will be better equipped to provide critical information and services to decision-makers, communities, Indigenous Peoples, and stakeholders grappling with and, in some cases benefiting from, rapid changes in the Arctic and their global implications.

Hover over each pulsing dot in the image below to view each component to NOAA’s strategy for Advancing scientific understanding and services in the Arctic.

Collaboratively Manage and Store Data in Alignment with FAIR and CARE Principles

Foundational Science and Data that Informs and Motivates a Robust Observation Network

Outcomes from Foundational Activities are Collaboratively Feed into Scientific Analysis, Modeling, and Predictions

Exchange Knowledge with Arctic Partners to Collaboratively Refine Research Questions, and Co-Develop Tools, Products, and Services that Empower Communities

Figure 2. Cyclical depiction of NOAA’s foundational science activities. Each component feeds into the next, with the circle reflecting how knowledge generated through foundational science, analysis, and input from Arctic Partners will identify further gaps and inform subsequent foundational science activities. View full image.

- Increasing the capacity of the observational community – The United States Arctic Observing Network (U.S. AON) brings together Federal agencies and non-Federal partners to understand and improve scientific observations and observing platforms in the Arctic. Supported by the Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Arctic Research Program, U.S. AON works internationally through the Sustained Arctic Observing Network.

- Ocean and marine observations – Decades of repeat survey data provide valuable information to inform laboratory and modeling analyses, and advanced understanding of key Arctic processes. Research programs supported by NOAA sustain integrated physical, biological, and chemical observations in the Arctic, including the Arctic Marine Biodiversity Observation Network, the Distributed Biological Observatory, and the OAR-NMFS Ecosystems and Fisheries-Oceanography Coordinated Investigations.

- Atmosphere observations – Long-term research-quality monitoring at the Barrow Atmospheric Baseline Observatory is maintained by OAR’s Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML). More than 200 measurements including greenhouse gases (GHGs) are collected and BRW hosts research projects from around the world. Near Fairbanks, Alaska, GML and NESDIS support continuous ground-based measurements of GHGs. And, through U.S. Coast Guard support in Kodiak, Alaska, regular aircraft survey flights measure GHGs across boreal and tundra regions.

- Integrated Modeling – OAR Laboratories, NOS, NWS, and NMFS have focused on bringing the best available science to improving weather-, seasonal-, ecosystem- and climate-scale predictions of Arctic systems, including Arctic sea ice (see Goals 2 and 3). Improvements include introducing updated ocean, atmosphere, land, and ice processes, enhancing regional-scale models; advancing fully-coupled deterministic forecasting (e.g., NOAA’s Unified Forecast System); delivering a next-generation seasonal-to-decadal prediction system (e.g., Seamless system for Prediction and EArth system Research); and assimilating satellite sea ice concentration and thickness observations supported by NESDIS.

- A March 2024 Interagency Working Group on Ocean and Coastal Mapping report20 revealed the Arctic Portion of U.S. waters in the Alaska region is 73 percent unmapped. While significant gaps persist, increased partnerships and advancements in collection systems have greatly improved acquisition efficiency in recent years (see Goal 6). NOAA ships and contractors are utilizing multibeam echosounders and topobathymetric LiDAR that are married together to produce seamless elevation models, uninterrupted topobathymetric surfaces that are critically needed to provide accurate maps and map-based services to coastal areas in the Arctic.

- NOAA’s NOS, through the National Water Level Observation Network, is improving predictions of coastal change that are urgently needed to inform decisions of vulnerable coastal communities in the Arctic. As an implementing partner to the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System, the Alaska Ocean Observing System’s Alaska Water Level Watch is helping to fill observing gaps, which in turn increase forecasting capacity and access to near real-time coastal and ocean water level data, all while packaging this information in useful ways to support the needs of stakeholders (see Goals 5 and 6).

- National Weather Service (NWS) Alaska Region offices have developed critical partnerships to ensure that weather, water, and climate information is communicated effectively to decision makers in locations from Anchorage to remote coastal villages. To address gaps in science and technology, the Arctic Testbed and Proving Ground facilitates the testing and evaluation of new research, forecast techniques, products, and services to improve forecast process and decision support activities in Alaska and the Arctic and has developed partnerships with researchers to address forecasting challenges from aviation to freezing spray to sea ice prediction.

- NOAA spearheads the Earth Prediction Innovation Center, which is designed to ensure the Unified Forecast System (UFS) is an efficient, effective, and accessible community modeling system. The Arctic is an area of opportunity for the UFS community of developers and the broader research community to leverage each other by adopting this framework for coupled model development over the Arctic.

- NOAA maintains an exhaustive constellation of satellites both in low Earth and geostationary orbits with visible and infrared radiometers. Many operational products and climate data records are archived at the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), accessible by end users and Application Program Interfaces.

- End users can access data in advanced interfaces such as PolarWatch, a cross-NOAA program curating and providing cryosphere remote sensing data, user engagement, and training, thereby extending the exploitation of NOAA’s satellite information products and services. There is a fundamental need to improve the accuracy of global satellite-based observations at the high latitudes, including the Arctic.

- Arctic marine research is consistently supported by two NOAA ships homeported in Alaska, NOAA Ships Oscar Dyson and Fairweather, with additional support of ships from the contiguous United States. Creation of the Uncrewed Systems Operation Center in 2020 expanded NOAA’s capacity to gather critical air and marine observations and provide increased domain awareness in Alaska and the Arctic.

- NOAA aircraft routinely support marine mammal monitoring and the NWS. New aircraft coming to NOAA’s fleet — including two G-550s and two C-130Js — will also greatly enhance NOAA’s scientific capabilities in a changing Arctic.

Infrastructure and Ships of the Future

Welcoming NOAA Ship Surveyor and NOAA Ship Navigator

Research in the Arctic requires platforms such as ships, planes, laboratories and other infrastructure that are either designed or adapted to harsh conditions, including vast areas of seasonally and perennially ice-and snow-covered ocean and land.

NOAA Ships Rainier and Fairweather have worked primarily in Alaska and the Arctic charting the ocean floor and shoreline to provide tools for safe navigation for more than 55 years. In 2027 and 2028, two new vessels, NOAA Ship Surveyor and NOAA Ship Navigator, will take on this mission and push further North, mapping the opening Arctic to ensure safe navigation for commerce in the nation. NOAA will continue to work with the U.S. Coast Guard to optimize science requirements on the Nation's upcoming fleet of icebreakers. When crewed ships and aircraft are unable to meet data needs, OMAO will explore using uncrewed systems to make environmental observations. In multiple instances already, OMAO has helped agency partners more efficiently or safely gather data, and reach previously inaccessible regions in Alaska and the Arctic.

Infrastructure and Ships of the Future

Welcoming NOAA Ship Surveyor and NOAA Ship Navigator

Research in the Arctic requires platforms such as ships, planes, laboratories and other infrastructure that are either designed or adapted to harsh conditions, including vast areas of seasonally and perennially ice-and snow-covered ocean and land.

NOAA Ships Rainier and Fairweather have worked primarily in Alaska and the Arctic charting the ocean floor and shoreline to provide tools for safe navigation for more than 55 years. In 2027 and 2028, two new vessels, NOAA Ship Surveyor and NOAA Ship Navigator, will take on this mission and push further North, mapping the opening Arctic to ensure safe navigation for commerce in the nation. NOAA will continue to work with the U.S. Coast Guard to optimize science requirements on the Nation's upcoming fleet of icebreakers. When crewed ships and aircraft are unable to meet data needs, OMAO will explore using uncrewed systems to make environmental observations. In multiple instances already, OMAO has helped agency partners more efficiently or safely gather data, and reach previously inaccessible regions in Alaska and the Arctic.

Five-year Strategy: The activities laid out in this goal will form the cornerstone of each subsequent goal in this Vision and Strategy. Over the next five years, targeted research to fill gaps in foundational data and modeling capability, bolstered investments in observing and modeling platforms that includes the integration of emerging technologies, and enhanced data management will be essential elements strengthening the foundational science required to monitor and understand the rapidly changing environmental conditions in the Arctic. This goal responds to the key science questions identified in the Introduction.

Develop and embrace emerging technologies and observing platforms: Increase the coverage and number of foundational observations and data needed for more refined models and forecasts. Deploying emerging technologies will ensure NOAA’s capacity to move foundational Arctic science forward, with support from community science, advancements in areas such as uncrewed systems, satellite technology, new in situ ocean and atmosphere observation sensors, omics, eDNA, artificial intelligence, and machine learning will help NOAA inform and support foundational science in the Arctic, gather more data and provide updated decision support products to NOAA partners throughout Alaska and the Arctic.

NOAA recently announced $1.8 million for three new awards to support the development, procurement, and deployment of innovative ocean monitoring technologies in the Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Arctic Research Program. This will support three-year innovative ocean observing infrastructure projects, specifically investing in: 1) building NOAA’s contribution to Argo in the Arctic, ocean instruments for measuring subsurface water profile data including under sea ice, which is in collaboration with the Office of Naval Research, 2) increasing ice-responsive monitoring systems in the Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas through the EcoFOCI research program, and 3) deploying additional Seasonal Ice Mass Balance Buoys in the high Arctic.

An expanded Arctic observing footprint will also better prepare NOAA to provide critical services and address issues at the local community level. Difficulties still remain such as dissemination outages in the automated surface and weather observing systems with Federal partners, such as the Federal Aviation Administration. OAR’s Global Monitoring Laboratory is working with commercial airlines that make frequent flights throughout the Arctic to permanently install monitoring systems for greenhouse gases and trace gases that will enable early detection of sudden emissions changes. The NWS Alaska Region has proactively addressed both current and emerging operational forecast gaps by establishing and resourcing the Alaska Environmental Science and Service Integration Center, which will allow NOAA to better meet current and emerging cross-cutting needs of partners, customers, and stakeholders in Alaska, as well as those that operate in Alaska waters.

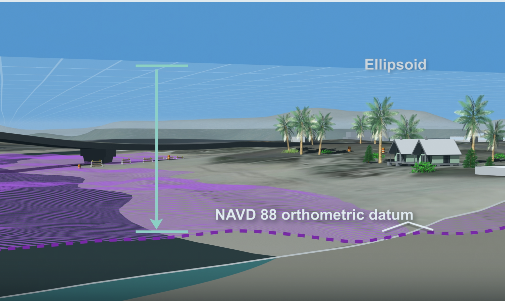

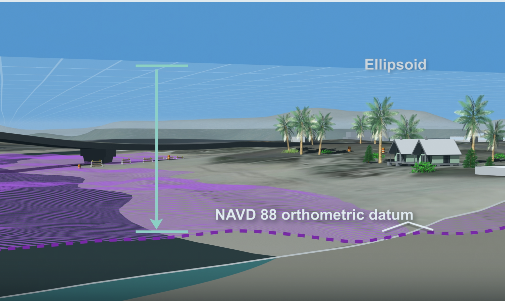

Vertical Datum Transformation (VDatum)

Integrating America's Elevation Data

Complementary to the Arctic mapping and observing priorities noted in this goal, completing a statewide tidal to vertical geodetic datum transformation tool (VDatum) is a critical requirement for developing many desired NOAA products and services such as integrated water prediction, flood mapping and forecasting, and sea-level rise visualizations. NOAA received funding in FY24 to support installation of infrastructure and water level and other satellite system observations to fill known data gaps and support VDatum model build-out in Alaska.

Vertical Datum Transformation (VDatum)

Integrating America's Elevation Data

Complementary to the Arctic mapping and observing priorities noted in this goal, completing a statewide tidal to vertical geodetic datum transformation tool (VDatum) is a critical requirement for developing many desired NOAA products and services such as integrated water prediction, flood mapping and forecasting, and sea-level rise visualizations. NOAA received funding in FY24 to support installation of infrastructure and water level and other satellite system observations to fill known data gaps and support VDatum model build-out in Alaska.

Ensure timely access to foundational data: Enable wide and rapid access of information for decision-making and analysis by all Arctic stakeholders, user groups, and communities. NOAA can demonstrate the agency’s commitment to providing broader, faster data access and enhancing collaboration in Alaska and the Arctic by following FAIR data principles that promote data sharing and stewardship. Current examples, such as Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing’s Arctic Research Program data landing pages and PolarWatch can serve as models to follow and scale up across all of NOAA’s Arctic activities and programs. Further, NOAA will invest in CARE principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Foundational data management must also align with CARE principles to protect data sovereignty and ethically engage with Indigenous and Tribal communities to support informed decision-making and climate resilience. The current data gaps limit NOAA’s understanding of Arctic-global climate linkages, impacting its ability to fully support this important region.

Transform foundational data into action: Co-design NOAA’s core observation, analysis, and products with communities to achieve a resilient and thriving Arctic. NOAA’s foundational science activities are not complete until the results are communicated and used to deliver products, tools, and services that empower communities (Fig. 2). NOAA products, like the annual Arctic Report Card and Ecosystem Status Reports, translate science into actionable knowledge for local and regional communities. Coastal challenges are addressed in collaboration with extensive partner networks such as the Alaska Harmful Algal Bloom Network. Through the Kasitsna Bay Laboratory and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NOAA monitors coastal ecosystems and provides statewide technical assistance and forecasting tools to monitor the increasing climate changes in Alaska and the Arctic. In the coming years, NOAA will continue to engage regularly and meaningfully across partners (see Goal 4) and user-groups to collaboratively design data-driven weather and climate products and services that are most relevant and in demand by Arctic communities.

Through partnerships (e.g., private sector, local and Indigenous communities, interagency) (see Goal 4) and sustained investments in research and development, NOAA can widen the agency’s scope of atmospheric, oceanographic, ecological, and meteorological observations in the Arctic, and advance proof-of-concept applications into scalable, region-wide foundational science activities.

Goal 2: Monitor and Forecast Sea Ice

Figure 3. Monthly sea ice extent anomalies (solid lines) and linear trend lines (dashed lines) for March (black) and September (red) 1979 to 2023. The anomalies are relative to the 1991-2020 average for each month. Adopted from Meier et al. (2023)23.

Current Activities: NOAA leads comprehensive Arctic sea ice research, analyses, and forecasting efforts, addressing the complex challenges of a rapidly changing Arctic environment. NOAA activities encompass:

- Observations and Modeling – NOAA gathers extensive sea ice observations using its own satellite, airborne, and in situ observations, including from the U.S. Interagency Arctic Buoy Program and the Sea Ice Mass Balance Buoys through OAR, NESDIS, and NWS programs. NOAA’s observations and derived environmental information products feed into its regular sea ice forecasts and climate model evaluations. NOAA is advancing the integration of dynamic sea ice models into the coupled Earth System-based Unified Forecast System (UFS) to enhance Arctic predictions, working on improving in situ and remote sensing data assimilation techniques, developing common diagnostic metrics for model comparisons, and developing regional applications of the UFS for the Arctic. OAR’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) produces quasi-operational subseasonal-to-seasonal sea ice predictions based on global coupled dynamical models with data assimilation, which have skill on Pan-Arctic, regional, and local spatial scales. GFDL also produces decadal-to-centennial model projections of Arctic climate, using climate change ensembles to quantify forced changes and contributions from internal climate variability.

- Analysis and Forecasts – The NWS Alaska Sea Ice Program (ASIP) provides sea ice analyses, forecasts, monthly outlooks, and decision support services for Alaska waters, supporting entities around the state and nationally to support safe navigation, protect life and property, and enhance the national economy. ASIP works closely with the U.S. National Ice Center (USNIC), a multi-agency center comprising staff from the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Coast Guard, and the NOAA NWS Ocean Prediction Center Ice Services Branch. USNIC provides global- to tactical-scale ice and snow products and services to meet U.S. national interests with products including global sea ice analysis, forecasts and outlooks, and Great Lakes ice conditions.

- Data Products and Stakeholder Services – NOAA maintains critical data resources such as authoritative satellite Sea Ice Index and Climate Data Records and works on creating fit-for-purpose sea ice characterization products. These efforts support safe navigation, over-ice transportation, and subsistence activities. NOAA’s work extends to hazard monitoring and mitigation, providing product services and applications to inform users and partners with experimental and proven resources.

- Collaborative Approach and Knowledge Integration – NOAA works across Line Offices to analyze and align NOAA activities to address the needs of Tribal communities and stakeholders. NOAA collaborates with academic institutions, international partners, industry partners, and local communities to co-design and develop relevant sea ice products and services. This includes bringing together community-based observations, local ecological knowledge, and Indigenous Knowledge into NOAA’s monitoring systems.

Community Spotlight

Sea Ice for Walrus Outlook (SIWO)

For more than a decade, the NWS Alaska Sea Ice Program and Fairbanks Weather Forecast Office have jointly produced the SIWO, working collectively with the Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., the Eskimo Walrus Commission, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and Bering Strait native communities. The SIWO provides weekly reports each spring with weather and sea ice conditions for the Bering Strait Region. The NWS will continue to support this joint effort, which highlights how Alaska Native subsistence hunters, researchers, and NOAA can come together to meet emerging community needs.

Community Spotlight

Sea Ice for Walrus Outlook (SIWO)

For more than a decade, the NWS Alaska Sea Ice Program and Fairbanks Weather Forecast Office have jointly produced the SIWO, working collectively with the Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S., the Eskimo Walrus Commission, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and Bering Strait native communities. The SIWO provides weekly reports each spring with weather and sea ice conditions for the Bering Strait Region. The NWS will continue to support this joint effort, which highlights how Alaska Native subsistence hunters, researchers, and NOAA can come together to meet emerging community needs.

Five-year Strategy: NOAA’s five-year strategy for Arctic sea ice monitoring, forecasting, and services is built on key activities identified through cross-agency engagements. The focus is on increasing observations, enhancing data services, developing user-centric decision support products, and advancing modeling and forecasting capabilities. Together, these elements will provide more accurate and useful sea ice information to inform stakeholders and the scientific and operations communities on how the Earth system evolves in high northern latitudes, enabling a Weather-Ready and Climate-Ready Nation:

Adopt a user-centric approach to co-design the development of sea ice products and services and their efficient access: Conduct a thorough assessment of user requirements, including Line Office operational needs and community priorities. This approach will guide the development of these products and services, ensuring they directly address the evolving needs of Arctic communities, maritime operators, resource managers, and policymakers. NOAA aims to create a pathway to co-develop new products and deliver services that support safe operations, ecosystem management, and climate-ready decision-making.

Coordinate sea ice observations and data services: Emphasize the integration and enhancement of NOAA observational capabilities. NOAA will develop a comprehensive sea ice in situ observing strategy that maximizes the use of satellite data while incorporating community-based observations and local and Indigenous Knowledge. By establishing intra- and interagency coordination for strategic investment in observations and technologies enabling future observations, NOAA will create more robust and interconnected data systems and data management efforts that mitigate existing known science gaps. This includes integrating atmospheric, oceanic, and sea ice observations, as well as developing standardized data assimilation pathways and quality control measures across NOAA line offices. Archiving historic datasets, which are crucial for long-term climate monitoring and model validation, is also a priority.

Innovate to create novel, fit-for-purpose sea ice products and application services: Strengthen the synergies between observations, product services, and numerical prediction by addressing user needs and recommendations identified in NOAA strategic documents (e.g., Weather Water Climate Strategy) and by other governmental organizations and international bodies, with a specific focus on sea ice dynamics, sea ice long-term records, and product enhancements to address gaps that will enable NOAA to deliver U.S. Government authoritative products and services of the highest quality.

Initiate strategic alignment to leverage the full potential of NOAA’s capabilities: Develop solution-based working groups and strengthen engagement across the agency. Aligning these efforts will accelerate knowledge transfer and enhance NOAA’s ability to deliver impactful Arctic products and services. This strategic alignment will shorten the transition of processes to operations, ensuring that scientific advancements translate rapidly into operational improvements. NOAA will continue to lead collaborative efforts like the Sea Ice Outlook, working with international partners to refine its ability to provide daily and seasonal to decadal forecasts based on the latest observations and analyses.

Improve modeling and forecast delivery: Crucial to meeting the increasing needs in the Arctic, NOAA will invest in developing and refining coupled atmosphere-ice-ocean-wave models, with a focus on improving short-term forecasts, and ensemble-based seasonal and long-term projections. Key initiatives include integrating sea ice models into the Unified Forecast System (UFS), improving data assimilation techniques for higher latitudes, and developing common validation metrics for rigorous model comparison. The UFS implementation marks a pivotal shift in NOAA’s operational forecasting capabilities and will drive critical innovations in product development and validation over the next five years. The Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory is actively developing next-generation sea ice, ocean, atmosphere, and land models, developing novel techniques for sea ice data assimilation, evaluating subseasonal-to-seasonal prediction skill, submitting predictions to the Arctic Sea Ice Outlook, and researching the inherent predictability of Arctic sea ice. To enhance these efforts, NOAA is leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques to optimize data assimilation and satellite data analysis, enhance predictive capabilities, and accelerate forecast generation and delivery. Successful application of artificial intelligence techniques relies on expanding critical Arctic observations as laid out in Goal 1. NOAA will focus on reducing uncertainties in multi-seasonal and multi-decadal climate projections, particularly in relation to anthropogenic forcing and natural variability in the Arctic. This effort will involve a comprehensive evaluation of climate models, including those featured in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Reports, and developing specialized high resolution regional models that capture Arctic-specific processes more accurately than global models alone.

NOAA Arctic Sea Ice Observing Systems

How We Study Arctic Sea Ice Dynamics

This figure illustrates the diverse monitoring techniques (red icons) employed to study Arctic sea ice dynamics and related environmental processes. These integrated observing systems provide crucial sea ice data to support decision-making across various scales and domains (Adapted from Roberts et al., 201026). View full image.

NOAA Arctic Sea Ice Observing Systems

How We Study Arctic Sea Ice Dynamics

This figure illustrates the diverse monitoring techniques (red icons) employed to study Arctic sea ice dynamics and related environmental processes. These integrated observing systems provide crucial sea ice data to support decision-making across various scales and domains (Adapted from Roberts et al., 201025). View full image.

Goal 3: Improve Weather, Water, and Climate Forecasts, Warnings, and Impact-Based Decision Support

Goal Statement: To provide timely and accurate forecasts, warnings, and decision support that ensure communities and stakeholders in the Arctic are ready, responsive, and resilient to environmental impacts resulting from weather, water, ice, and climate-dependent events.

Strategic Importance: Weather, water, and climate all impact daily decisions made by individuals gathering food on land and water, vessel operators planning voyages and en-route navigation, and emergency managers preparing for the next big environmental hazard. As a world leader in weather and climate science and services, NOAA provides timely and actionable environmental information that is the basis for smart policy and decision-making in a changing Arctic.

With parts of Alaska seeing more than 70 feet of coastal erosion per year, in addition to considerable river erosion, communities require more advanced forecasting to address numerous localized weather and climate impacts. Critical global shipping arteries in Alaska waters are impacted by changing sea ice conditions, freezing spray, and extreme wind and wave hazards, requiring accurate warnings and forecasts. NOAA contributes to interagency needs, supplying vital data to partners such as the U.S. Coast Guard, Department of Defense, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, as well as the State of Alaska Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. Actionable weather and water information for planning and decision-making are required to protect lives, property, and manage the region’s many resources.

Arctic populations rely on aviation and marine systems more than road systems for transportation and access to goods and services. Remoteness, limited observations, and extreme weather make air and sea travel in the region inherently more dangerous than in the contiguous United States. A changing climate exacerbates many environmental challenges such as reduced visibility due to thick wildfire smoke and increased low clouds and low visibility in fog for coastal communities brought on by reduced sea ice. Environmental observations and studies supporting weather and ice forecasts are highly limited in both geographic scope and frequency. Further improvements in weather and water observations and research will combat these challenges and strive to increase safety and efficiency in these important sectors. For example, there are many real-time environmental data gaps lacking sufficient resolution and fidelity, including bathymetric maps, in U.S. Arctic waters to support accurate forecasting of fall sea storms and coastal erosion, which threaten marine transportation, offshore oil and gas operations, and Arctic coastal communities.

Climate change is also affecting the Arctic environment, as evidenced by changing precipitation patterns, later freezing and earlier thawing of snow and ice, and changing sea level. People living along rivers and inland waterways face increasing disruption due to more frequent and devastating flooding and erosion. Wildfires over the years have also expanded to more tundra locations, presenting air quality and infrastructure hazards not previously experienced. Still others face drought, straining municipal water supplies that increase community risk. Alaska’s strategic location and waterways present both challenges and opportunities in terms of marine transportation, homeland security, and economic development. Further improvements in monitoring critical climate regions, research on how to better predict long-term changes, and improved modeling for products on sub-seasonal to climate timescales will aid communities to prepare for and respond to the challenges and opportunities as they arise.

Current Activities: NOAA provides weather, water, and climate data, forecasts, warnings, and impact-based decision support services to protect life and property and enhance the national economy. Integrated environmental information and predictive services are provided for a multitude of hazards including marine weather, coastal floods, sea ice, river flooding, glacial lake outburst floods, winter weather, fire weather, tsunamis, aviation weather, volcanic ash, climate, and space weather.

- National Weather Service Offices in Alaska – The NWS in Alaska operates several specialized offices and units in addition to its core Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs) and Weather Service Offices (WSOs). These include the Alaska-Pacific River Forecast Center, which focuses on river breakup and flooding, and river and stream water level forecasting; the Alaska Aviation Weather Unit, providing critical aviation forecasts; the Anchorage Volcanic Ash Advisory Center, which monitors and issues warnings about volcanic ash that can impact aviation and public health; the Alaska Sea Ice Program, which analyzes and forecasts sea ice conditions across Alaska waters; and the National Tsunami Warning Center, which provides tsunami monitoring and warning services for the Continental United States, Alaska, and Canada. The NWS also operates the Alaska Regional Operations Center (ROC), which serves as a coordination hub for regional weather events and emergency response. Major WFOs are located in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau, while smaller WSOs, such as those in Utqiaġvik (Barrow), Nome, Kotzebue, and Yakutat, offer localized weather data collection and services.

- NOAA weather, water, and climate Social Science efforts – Social scientists, particularly in Utqiaġvik, Nome, and Bethel, play a role in enhancing communication with Indigenous communities by tailoring weather forecasts, warnings, and sea ice information in culturally appropriate ways. This integration of social science helps the NWS improve the delivery of critical forecasts to communities that rely on timely, actionable information for subsistence activities and safety, especially with rapidly changing sea ice conditions.

- Improvements to NOAA modeling capabilities – Efforts at OAR’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Physical Sciences Laboratory, and Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory are bringing the best available science to improving coupled and regional weather-, seasonal-, and climate-scale predictions of the Arctic system and Arctic sea ice (see Goals 1 and 2). These improvements help underpin the next generations of NWS models and IPCC climate change assessments for policy and decision makers.

- National Weather Service National Centers – NWS Alaska also works closely with the NWS National Centers for Environmental Prediction, including the Climate Prediction Center, the Ocean Prediction Center and its U.S. National Ice Center, and the Environmental Modeling Center to provide Arctic-specific weather, water, and climate predictions and services. Through partnerships with national centers, local expertise, and community collaboration, NWS Alaska delivers vital services to help residents navigate the region’s extreme and rapidly changing conditions.

River Watch Program

Working alongside Alaska Native communities to support resilience

The NWS Alaska-Pacific River Forecast Center works with Alaska Native communities, local pilots, and the State of Alaska to monitor river ice conditions and provide accurate river breakup forecasts and warnings for remote Alaska communities. As NWS hydrologists arrive in communities they meet with local Tribal councils, village chiefs, and city managers to ensure decision support needs and Indigenous Knowledge are heard and understood. Oftentimes an Alaska Native Elder will join staff on flights to share knowledge and relay observations by marine radio to community members listening below. This collaborative effort supports remote Alaska community resilience in a changing Arctic.

River Watch Program

Working alongside Alaska Native communities to support resilience

The NWS Alaska-Pacific River Forecast Center works with Alaska Native communities, local pilots, and the State of Alaska to monitor river ice conditions and provide accurate river breakup forecasts and warnings for remote Alaska communities. As NWS hydrologists arrive in communities they meet with local Tribal councils, village chiefs, and city managers to ensure decision support needs and Indigenous Knowledge are heard and understood. Oftentimes an Alaska Native Elder will join staff on flights to share knowledge and relay observations by marine radio to community members listening below. This collaborative effort supports remote Alaska community resilience in a changing Arctic.

Five-year Strategy: NOAA will focus on ensuring Arctic communities and stakeholders are ready, responsive, and resilient to environmental impacts resulting from weather, water, ice, and climate-dependent events.

Improve NWS infrastructure to be resilient and reliable, ensuring access to technology and tools that enable NWS personnel to provide weather, water, and climate services to decision makers anytime, anywhere: Modernize and simplify weather.gov to improve its value, stability, and user experience, supporting all communities including those in remote areas of Alaska. NWS will also continue advocating for infrastructure improvements through Federal channels to accomplish goals such as improving reliability of weather observations and in broader national infrastructure initiatives. The NWS will develop products and services guided by social science, exercises, outreach, and partnership building to provide relevant and appropriately timed information and decision support services, including driving an expansion of accurate forecast information and messaging for weekly, monthly, and seasonal lead times that is relevant and actionable for users or partners in Alaska.

Build and operate the world’s best community-based and cross-platform numerical Earth modeling system with advanced ensemble prediction capabilities at all timescales and sufficient spatial accuracy: This will be achieved through collaboration with NOAA’s Enterprise partners, including private meteorological companies, research institutions, and universities, all contributing to advancing weather prediction, communication, and decision support. This will improve forecast accuracy in extended time frames, which in turn will provide more actionable warnings for those in Alaska needing additional time to make preparations ahead of extreme conditions.

Complete VDatum, enabling NOAA to provide coastal inundation forecasts and warnings: This action, to be completed by NOS working with the State of Alaska (see Goal 1), will also establish the geospatial foundation to enable use of NOAA’s suite of digital coast tools. The NWS will also deliver actionable inland and coastal water resource and inundation information across all timescales and appropriate spatial scales. This will address the growing risk of flooding, drought, and low water flow as well as immediate and long-range water management and planning. In addition, the agency will build expertise and tools to increase its capacity to understand, interpret, and communicate forecaster confidence to drive probabilistic impact-based decision support services at lead times beyond one week.

Goal 4: Enhance Partnerships - International, National, Regional, and Local

Goal Statement: To work closely with international, national, regional, and local partners to promote cooperation and sharing of data, observational platforms, and intellectual resources to enable more rapid and comprehensive attainment of NOAA’s Arctic science and ecosystem-based management goals, and contribute to the U.S. Government’s goal of a peaceful, stable, prosperous, and cooperative Arctic region.

Strategic Importance: Increased variability in the Arctic environment is impacting the globe and its connectedness, resulting in a changing geopolitical landscape and impacting national security. NOAA is one of the primary Federal agencies present in the Arctic, making it vital that NOAA continue to build on its abilities to observe, understand, predict, and respond to Arctic changes. The complexity and rapidness of change is beyond the capacity of a single agency or nation. Therefore, local, regional, national, and international partnerships are needed to observe the environment, improve analyses and forecasts, and apply ecosystem-based management that is adaptable to future rapid change.

Current Activities: NOAA leads and provides key support to high-level national and international partnerships focused on the Arctic and its people. NOAA’s activities encompass:

- Whole-of-government strategies and implementation plans – The National Strategy for the Arctic Region (NSAR), updated in 2022, serves as a framework to guide the U.S. Government’s approach to tackling emerging challenges and opportunities in the Arctic, with a focus on four key pillars: 1) Security, 2) Climate Change and Environmental Protection, 3) Sustainable Economic Development, and 4) International Cooperation and Governance. NOAA is the lead agency for several of the NSAR’s strategic objectives and is a co-lead for the Climate Change and Environmental Protection pillar.

- Interagency partnerships – NOAA is actively engaged in the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee (IARPC), which consists of 18 U.S. agencies, departments, and offices across the Federal Government, and implements the IARPC Arctic Research Plan that outlines a vision for Federal agencies to address emerging research questions. The plan also provides pathways to strengthen relationships between Federal agencies and Indigenous communities, academia and non-Federal researchers, the State of Alaska, nonprofits, and private sector and international organizations. NOAA co-chairs some of the IARPC Collaboration Teams and is a co-chair of the U.S. Arctic Observing Network Board, which is developing a national approach to observing in the Arctic and contributing to the international efforts of Sustaining Arctic Observing Networks. NOAA also plays an agency principal role in the U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System Safety Arctic Integrated Action Team, where a group of interagency partners coordinate transportation policies in the U.S. Arctic to improve the safety and security of the marine transportation system. NOAA contributes to the U.S. National Ice Center, bringing together NOAA, Navy, and the U.S. Coast Guard to support the entire U.S. Government in need of global sea ice operational analyses and forecasts. Other interagency and national partnerships include the U.S. Coast Guard, NASA, DOD, DOI/USGS, Department of State, NSF, U.S. Army Research Commission, University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System, and Tribal entities such as the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and NOAA Tribal liaisons.

- Regional and Local Partnerships – Seascape Alaska is a regional partnership to advance foundational seafloor and coastal mapping activities. The Alaska Mapping Executive Committee is co-chaired by NOAA and the Department of the Interior and provides a mechanism for Federal agencies to collaborate and address the challenge of delivering geospatial data access in Alaska, where conservation, climate change, safety, economic, and national security interests intersect. The NOAA Regional Collaboration Network Team in Alaska assists with identifying, communicating, and responding to regional needs by catalyzing collaboration and connecting people and capabilities to advance NOAA’s mission and priorities.

- Multilateral International Partnerships – NOAA participates in numerous international organizations, regional fisheries management organizations, and multilateral bodies such as the Arctic Council. NOAA representatives engage in four of the six Arctic Council Working Groups – Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program, Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Emergency Prevention, Preparedness, and Response, and Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) – and serve in leadership roles (e.g., Head of Delegation and Expert Group co-chairs) in PAME. NOAA leads the delegation to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, which is engaged on some Arctic issues, including in cooperation with the PAME. NOAA represents the United States in the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and at the International Hydrographic Organization, with contributions in several Arctic focused committees, such as the WMO Advisory Group for the Global Cryosphere Watch, the Expert Team on Sea Ice Watch, and the International Maritime Organization. NOAA is considering the best approaches to engage and support the upcoming International Polar Year in 2032, led by the International Arctic Science Committee and WMO. The NOAA Office of Coast Survey will co-chair the Arctic Regional Hydrographic Commission starting in 2025. The United States is also party to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement to which NOAA is the lead agency (see call-out box) and the Search and Rescue Satellite Aided Tracking program as the United States lead, which plays a vital role in the emergency response notification for vessel and aircraft accidents in the harsh conditions of the Arctic. NOAA contributes to three agreements under the Arctic Council: The Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation, the Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic, and the Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic.

- International Ice Service Cooperation – NOAA also contributes to the North American Ice Service as well as the International Ice Charting Working Group, an advisory group to the WMO.

- Bilateral Partnerships – NOAA also has Arctic-focused bilateral agreements and engagements with Canada, Finland, Norway, the European Union, South Korea, and Japan, among others. NOAA currently cooperates with other governments through broad Science and Technology Agreements and NOAA-specific agreements, as well as through international institutions and organizations. Memorandums of Understanding with Arctic States and non-Arctic States support NOAA’s work in the Arctic regarding weather, climate, aviation, and marine observations, navigational safety, forecasts, and services; ecosystem management; fisheries; and ice monitoring. These agreements allow NOAA to cooperate on sea ice forecasts, as well as better understand and predict changes in the Earth’s environment by observing the Arctic atmosphere and cryosphere from manned observatories in places such as Summit, Greenland.

CAOFA and Tribal Engagement

Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean

The United States is Party to the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, which entered into force in 2023 and aims to prevent unregulated fishing and applies precautionary conservation and management measures as part of a long-term strategy to safeguard healthy marine ecosystems and to ensure the conservation and sustainable use of fish stocks.

NOAA leads the U.S. delegation for this international agreement. It is the first regional fisheries agreement that applies a precautionary approach before commercial fishing begins, rather than after a fishery collapse. This forward thinking will ensure that adequate data on human impacts is collected. It is also the first agreement to require the inclusion of scientific research and Indigenous Knowledge to inform decision-making.

Representatives from the Inuit Circumpolar Council, Alaska, serve as members of the U.S. delegation alongside representatives from NOAA, Department of State, and the U.S. Coast Guard. Additionally, NOAA has participated in local and regional briefings in Alaska about the Agreement, its impact, and to seek input into the U.S. delegation’s positions to ensure Indigenous perspectives are reflected by the United States during negotiations. This ensures strong representation of groups facing the bulk of climate impacts but which have been historically overlooked on the national and international stage.

Five-year Strategy: With the impact of climate change becoming more dramatic in the Arctic, national and international partnerships are vital to crafting adaptive policies for a rapidly changing geopolitical and environmental landscape. Through these changes, Indigenous Peoples are at the forefront, are the first to see the impacts, and hold many of the solutions needed to address these changes and to understand them. NOAA will continue to support these relationships through partnerships, formal arrangements, and and and co-stewardship agreements. Understanding and predicting environmental changes, such as sea ice cover and consistency, weather forecasting, and improved climate modeling in the Arctic necessitates cooperation. The Arctic Council is of notable importance, and NOAA will continue to contribute to key U.S. Government strategies and plans to ensure its ongoing success and viability. NOAA should continue its interagency and international partnerships to increase the accuracy, timeliness, and coverage of key contributions, such as sea ice and weather forecasts, ensuring seamless transitions across jurisdictional boundaries and enhancing safe navigation. NOAA should also formalize coordination with DOD to collect and disseminate critical environmental information, aiming to enhance domain awareness and improve DOD operability.

Strengthen Arctic protection mechanism at the international level: The reduction of sea ice opens new opportunities for trans-Arctic shipping, increased oil and gas exploration and extraction, tourism, commercial fishing, and other uses that increase regional vessel traffic, as well as associated threats such as risks to national security, oil spills, transport of invasive species, collisions with animal species or small craft, and disruption of food security activities within Indigenous communities. Working through the interagency process, NOAA will continue to strengthen Arctic protection mechanisms at the international level, including through vessel routing and reporting measures adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). This will require additional ice-breaking vessels to support the NOAA mission as well as continued partnership with the U.S. Coast Guard. Furthermore, NOAA will continue to develop and provide marine and ice weather services with the goal of preserving life and property in the Arctic.

Support Arctic governance, Indigenous governments and organizations, and science organizations: Changes in climate and sea ice are driving changes in marine ecosystems, species abundance, and composition, in ways not yet fully understood. NOAA will provide strong leadership and additional resources to support the Arctic Council and its working groups, which monitor and assess biodiversity, climate, and the health of humans and ecosystems. It will contribute to international approaches to ecosystem and protected area management, and management of shipping. NOAA seeks to work with the permanent participants representing Arctic Indigenous Peoples on the Arctic Council to identify how Indigenous and locally derived knowledge can help to understand and address changes in the Arctic in a holistic way. Other organizations, including the International Arctic Science Committee and the Pacific Arctic Group, identify science priorities across countries and build trusted and lasting relationships among scientists. The NWS Alaska Region is committed to coordinating with partners to use emerging technology, such as the National Water Model, to understand and predict environmental hazards, including those impacting ecosystems and food security. The NWS is also committed to developing new partnerships and enhancing existing ones with universities, Federal and state agencies, and other groups that have specific expertise in working with historically underserved and socially vulnerable communities on and off the road system.

Support the Sustaining Arctic Observing Networks (SAON) strategy for 2018-2028 to strengthen multinational engagement in pan-Arctic observing: A joint initiative of the Arctic Council and the International Arctic Science Committee, SAON will make achieving NOAA Arctic science goals more likely. NOAA will support developing an effective international SAON process (see Goal 1) that includes working with Indigenous Peoples to include Indigenous Knowledge where appropriate.

Continue coordination across Federal entities to implement overarching U.S. Arctic Policy goals: Coordination such as that provided by the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee is needed to meet U.S. goals, particularly those identified by U.S. Arctic Policy (National Security Presidential Directive 66 dated January 2009 and Homeland Security Presidential Directive 25 dated May 1994), the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force, and National Oceanographic Partnership Program. Scientific research and discovery will proceed in collaboration with the National Science Foundation, United States Geological Survey, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and other Federal, state, and local partners, academia, non-governmental organizations, and private entities. Due to the interconnected nature of Arctic ecosystems, the U.S. will also need to improve collaboration and engagement with other Arctic nations through international mechanisms, such as the Arctic Council and bilateral relationships, to better understand, observe, research, and manage Arctic resources.

Goal 5: Conserve and Manage Arctic Coastal and Marine Ecosystems and Resources

Goal Statement: To promote the stewardship, conservation, sustainable use, and ecosystem-based management of ocean and coastal resources based on the best available and evolving science, including Indigenous Knowledge, to support healthy, productive, and resilient ecosystems and communities.

Strategic Importance: With the Arctic in significant transition, it is increasingly important to address the local and regional needs of communities and the conservation and management of coastal and marine ecosystems on which they depend. Reduced seasonal sea ice and warming ocean temperatures, ocean acidification, and environmental hazards affect commercial, recreational, and subsistence fisheries and other resources. Species distribution and migration patterns continue to change as populations move northward and into foreign and international waters, with vast implications for living marine resources and the national economy, global relations, and local food security and cultures. Effects of these changes are currently being seen with the snow crab fishery collapse, greatly diminished chum and chinook salmon runs in western Alaska, walleye pollock populations shifting northward towards Russian waters, and Pacific cod abundance declines in a warming Bering Sea basin. At the same time, global governance structures and processes are altering seafloor claims, placing greater areas under U.S. jurisdiction and increasing the area of exclusive harvesting rights to benthic resources — both biotic and abiotic. Recognizing these threats, in 2009 the North Pacific Fishery Management Council implemented an Arctic Fishery Management Plan that precluded domestic fishing in Arctic waters until further information could be obtained. Additional governance measures and improved understanding of marine resources will be necessary under changing conditions (see Goal 4 call-out box for additional information about NOAA’s involvement in ecosystem-based management in international Arctic waters).

To support the understanding of changing Arctic marine ecosystems, and to mitigate impacts on food security of local communities, social wellbeing, and local and national economies, NOAA must expand its information gathering capabilities, frequency and footprint of monitoring, and assessments to adaptively manage and protect coastal and marine ecosystems and their available resources (see Goals 1-3). Management bodies will be required to consider additional and novel governance structures to ensure effective ecosystem-based stewardship, conservation, and sustainable future use of marine living resources in the Arctic. Enhanced partnerships will also be necessary to ensure broad understanding and appropriate application of conservation measures.

Current Activities: Much of NOAA’s marine resource assessment, research, and management falls within the purview of NMFS. However, additional data collection, observations, ecosystem studies, and modeling are all supported by efforts and infrastructure from across NOAA. Current activities include:

- Population Assessments and Ecological Process Studies – NOAA is continually advancing new methods and tools to improve resource assessments in challenging environments (e.g., using uncrewed air, surface, and underwater vehicles, omics). Ecological process studies and ecosystem interactions, as well as coupled ocean and atmosphere modeling efforts, conducted together with Arctic academic partners, contribute to improved resource management under rapidly changing conditions. For example, NOAA’s Ecosystems & Fisheries-Oceanography Coordinated Investigations (EcoFOCI) program is a joint research program between NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center and the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL), bolstered by additional observations of eDNA from PMEL and research from the Ocean Acidification Program. This joint program conducts ecosystem research in North Pacific and Alaska waters to determine the influence of the physical and biological environments on marine populations and the subsequent impact on fisheries. EcoFOCI scientists integrate field, laboratory, and modeling studies and work on seasonal, annual, and decadal timescales. Community science is also expanding along Arctic coastlines, especially in data-poor regions where local investment can bring valuable contributions to observation and monitoring. This includes the co-production of research with Indigenous communities, which is critical to successful stewardship of marine resources.